Italy’s new Cabinet is now three months old. The Five Star Movement-Lega coalition, which was sworn in in early June, has been described as the first fully populist government post-World War II Western Europe. Some analysts predicted that it would be short-lived, a Cabinet designed only to last through the summer. The Five Star Movement and the Lega, or League, party, so went the argument, were too different to stick together for long. The former is a nebulous group drawing most of its votes from the left and enjoying popularity especially among the unemployed in the less-developed south. The latter, based in the wealthy north, is a far-right party that emerged from the fringes by cannibalizing the mainstream right. The alliance seemed like a desperate move, forged hastily after months of unfruitful negotiations.

It now seems the populists are here to stay. The coalition is ranking high in the polls, as are both parties individually. What accounts for the solidity of this marriage between odd bedfellows? One possible explanation is that, despite their apparent differences, the Five Stars and Lega have a lot in common in terms of their peculiar approach to politics. Both parties claim to represent the true people against a decadent elite; both profess a disdain for professional politicians, an attitude described as “antipolitica,” or “anti-politics”; and both have been proponents of “giustizialismo,” or judicial zealotry – the sort of “lock them up” attitude linked to tough-on-crime crusades, never mind that both parties have had their own share of corruption scandals.

Of course, this raises the question of why Italy was so vulnerable to this style of populism in the first place. Some blame two decades of Silvio Berlusconi, the flamboyant tycoon-turned-prime minister who anticipated some of the eccentric leadership qualities of U.S. President Donald Trump. Others say it’s because, unlike Germany, Italy never fully confronted its fascist past. But the most persuasive argument is the least understood outside of Italy. It traces the roots of the present political climate to Mani Pulite, a corruption scandal that shook Italy’s political system 25 years ago.

***

From the end of World War II until the early 1990s, Italy had been consistently ruled by Christian Democracy, a centrist party that enjoyed America’s support, while the Communist Party, supported by the Soviet Union, was the main opposition force: It was a small-scale reproduction of the Cold War. Neither the Communists nor the Christian Democrats alone ever got close to get a majority in Parliament, but the latter could count on minor parties as allies: the Socialists, the Social Democrats, and the Liberals.

Corruption was endemic in the Christian Democracy party and its allies – and the Communists were no saints either – but the delicate equilibrium behind Italy’s mini Cold War rendered them untouchable, almost above the law:

“It was ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ that you couldn’t look into certain drawers. No one could open them, and when someone tried to, the drawers would immediately be closed again,”

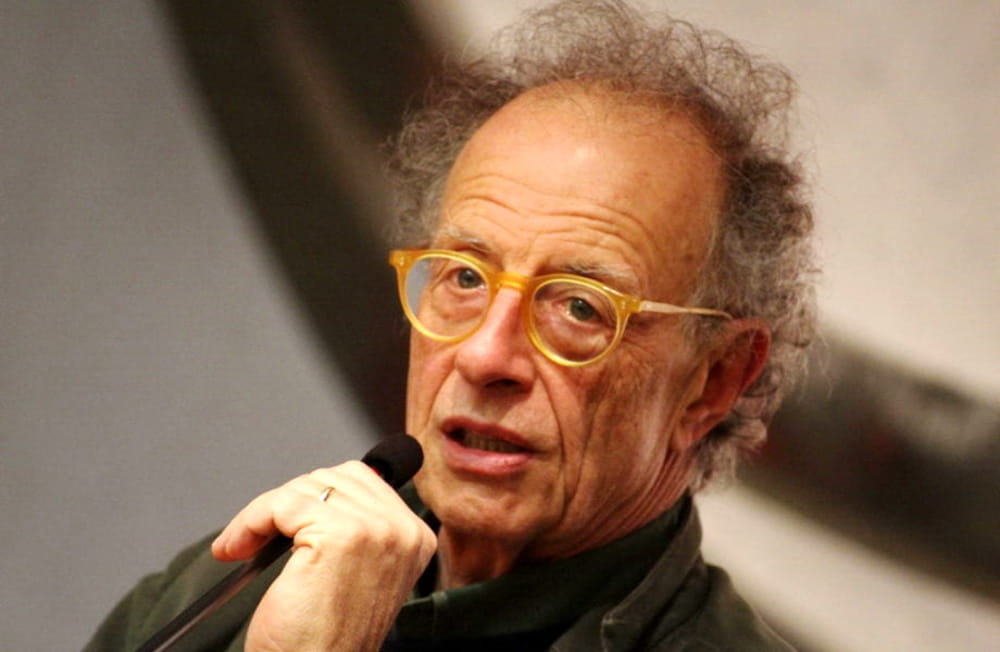

-Gherardo Colombo, one of Mani Pulite’s top judges, wrote in his 2015 memoir.

But when the Berlin Wall fell, the parties lost their invulnerability. The decisive corruption scandal erupted in early 1992, when an entrepreneur in Milan, Luca Magni, refused to pay a bribe to a Socialist politician: Instead, he reported him to the police, something unthinkable a few years prior. A pool of three prosecutors in Milan—Colombo, Piercamillo Davigo, and Antonio Di Pietro—started investigating and uncovered a system of institutionalized kleptocracy: All major parties were using bribes to finance their activities. Within three years, more than 3,000 people, mostly politicians and businessmen, were indicted in Milan alone—1,200 of them were eventually convicted. And all of Italy’s major parties were gone for good: the Christian Democrats and their allies swept by the scandal, the Communists by the Soviet collapse.

Mani Pulite spanned several years, but its most crucial year was 1993, when the powerful Socialist leader Bettino Craxi was indicted. By then, the investigations had become extremely popular—and politicians extremely unpopular. Thousands of fans encouraged the prosecutors in Milan with fax messages, a popular movement nicknamed “popolo dei fax,” the fax people. When Craxi was first accused, a crowd gathered in front his residence in Rome and threw coins at him: “Will you take these, too?” they chanted mockingly. Craxi fled the country in 1995 and died in exile.

So, what does a 1993 corruption scandal have to do with the populists running Italy in 2018?

First, it created a political vacuum from which Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party and the Lega (back then the Lega Nord, or Northern League) emerged. But some commentators claim that the connection between Mani Pulite and today’s political zeitgeist is deeper. Pierluigi Battista, a centrist columnist at the Corriere della Sera newspaper, and Mattia Feltri, a liberal analyst for La Stampa, have both argued that the 1990s anti-corruption rage planted the seeds for the anti-elite rhetoric that has brought the current Cabinet to power.